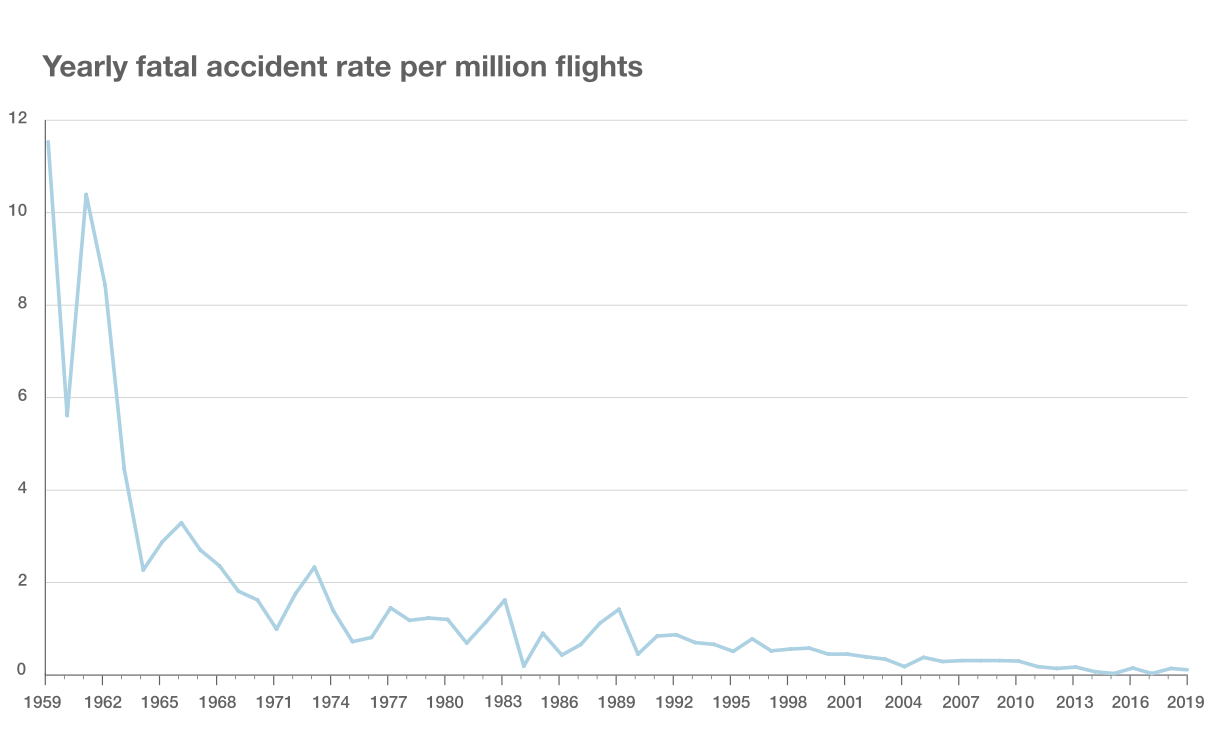

This is an amazing graph:

It describes the number of fatalaties arising from aviation accidents globally. In short it demonstrates that somehow we've managed to get to a place where it's normal to expect to get off a plane alive.

Which begs the question, how did this happen exactly? And how is that relevant to us?

In the early days of aviation one primary cause of accidents was technical: a cracked fuselage, engines dropping off, fuel running out, that kind of thing. Next came things like the weather, getting lost, hitting terrain, and technology took care of that. Which whittled it down to pilot error becoming the primary source of trouble.

As Malcolm Gladwell describes so well in his book "Blink", it became increasingly clear that something called "Cockpit Culture" was both the source of pilot error and, potentially, the answer.

When a pilot error originates with the junior members of a crew it would very often be caught and corrected by the more senior and experienced members. However, this was not readily reciprocated. Junior officers were terrified of their seniors (something called "power distance"). Even when they mustered enough courage to raise an issue, it was often brushed off, ignored or even angrily rejected. Rank has its privileges you know, and I'm not going to be lectured by some greenhorn straight out of school.

Accident investigators eventually collected enough data to drive changes in cockpit culture and more crews were trained on how to challenge each other productively, and especially, how to take the feedback. The whole thing was supported by a heavy emphasis on making it safe to discuss errors and mis-steps.

The result is really impressive: thousands of lives and billions of dollars saved, with no corresponding significant increase in safety costs, delays and son on. All it took was a change of focus in training and culture.

And this is not a one off. Similar results have been achieved in other professions by taking the same approach, from improving surgery outcomes to teaching police officers bystander skills.

For us, the lesson is simple: if we're going to have a culture of more accurate measurement, it must be safe to speak truth to power.

This is fundamental, and also very hard. There are many reasons we measure inaccurately, sometimes its technically hard and yet mostly it's because humans are very good at suppressing, ignoring, running from bad news. We learn this lesson early and well, so we can protect ourselves, from others who might wield the problem as a cudgel on us, from the worry of what will happen, from the damage to our reputation.

How can we address this very human problem of achieving safety?

First, we need a commitment from your organizations leaders to be great at giving and taking feedback, with safety top of mind. There are many ways to do this, but the short version is that when your people see and come to expect the highest standards of preserving safety, a culture of safety will slowly grow up.

Next, we need to

Some things can be given, and yet others can only be taken away.

Empowerment is a good example: one does not empower others, one simply stops disempowering.

And so it's the same with dignity, which can be nourished, valued and protected but never given, only taken.

As you may have realized by now, we're big fans of accurately assessing people's true potential. For this to happen, there must be a culture of openness.

(If you are curious why valuing dignity in an organization is a good idea, please read some of our the other articles on this site before reading further.)

There are four main behaviors which endanger Dignity, which are collectively known as 'ODHD', and we go into them in some depth below.

But why are these behaviors on the 'naughty' list?

Objectification is when we see our work relationships as somehow less subject to the rules we might use out of the office. This is most commonly an issue when when the two collide, for instance when two employees decide to have a consensual romantic relationship. If we work together, our roles become confused: am I talking to romantic partner or business colleague? And if one of the pair are senior to the other, is it really consensual? What about when it ends, do we behave differently than we would if we had dated someone outside the company? How do we deal with the after effects of break up?

It gets really complicated very quickly, and it's too easy for one or both to suffer the adverse affects of this: colleagues gossiping; bosses retaliating; you yourself unable to focus on our work.

The rock

As the child of two people who met in the office it pains me to say this, but there are literally billions of other people to date out there, romantic relationships are a big risk to one's own dignity as well as that of others, especially if you're more 'powerful' than them in the organization.

Dehumanization is when we treat our colleagues as if they were not really people. The most egregious example is when the phrase "it's not personal, it's only business is involved", for instance when headcounts are being reduced.

For anyone with a shred of decency, reductions-in-force (RIFs) are tough to carry out. It may be tempting to harden one's heart, pull the trigger and get them out as quickly and cleanly as possible, so one can stop thinking about them.

However, this can have two consequences: first, remaining staff will know how their recently departed colleagues were treated. The old adage "people might not remember what you did, but they will remember how you made them feel forever" seems apt. If you cut like crazy, ran folks out the door without a word, and paid them two weeks, people will know and take note of. And secondly, this is an easy way to begin the bad habit of ignoring that the folks you cut, even the most deserving ones, have some value to some enterprise somewhere. It's a slippery slope to viewing people simply as unpredictable machines.

One doesn't have to provide 6 months salary, a year's health plan and outplacement for another year to avoid the charge of dehumanizing. Recognizing that these are real people with real lives and real families, and there is a real and meaningful impact, will guide our behavior to a more empathetic place. Just like with an unexpected death in the family, checking in those affected will feel challenging to the giver and very supportive to the receiver.

It's not just extreme cases like RIFs where dehumanization can apply. Re-organizations of teams, even desk spaces, can be carried out in a dry, un-feeling way thanks to Excel. Simply (authentically) listening to people will help the people making the changes do it with more respect for the worth of the people affected.

Humiliation is the most obvious of the four. Any time a boss yells at an underling, especially in a group setting, will greatly diminish that individual. Psychologists will tell you that a firm and professional discussion in a private setting will get better results nearly all of the time.

But hold up here. It's also important to not go too far the other way. Avoiding humilation of our colleagues does not mean that we have to be nice, and avoid upsetting others at the same time.

If we are respectful yet firm in delivering feedback, bad news, even in challenging others, and they react negatively, that's on them. Our focus in on avoid a public humilation for those we work with.

Finally, degradation brings us to the challenge of asking others to carry out tasks that we ourselves would never want to do, to ask them to do things which do not recognize their unique talents, or are even morally, legally or ethically ambiguous.

The obvious ones here would be asking your assistant to go along with some suspect expense claims, stuff like that. However, what's less obvious is when we assume that some groups are there to serve us. Last century assumptions, such as asking the only woman in the meeting to get the coffee, may be clearly out of bounds today, and yet I wonder what might feel normal practice today that would be viewed the same way in a decade or two?